The Importance of an Integrated Quality Management System (QMS) and Safety Management System (SMS) in Aviation Operations

The relationship between a quality management system (QMS) and a safety management system (SMS) has developed into an insightful association in the aviation industry. The importance of their harmonious integration is becoming a crucial element in any successful flight operation. As SMS continues to evolve and become more regulated, it will take on a dominant role in a company’s overall strategy. Organizational leaders will need to direct their focus on how QMS and SMS can complement each other in the implementation and sustainment of their management system(s). Those leaders have the responsibility to establish the balance of production goals (delivery of services) versus protection goals (safety). If this integration does not result in meeting customer requirements, the organization will not survive the competitive pressures of today’s aviation environment.

Quality Management – A Foundation For Safety

ISO 9001:2008 (The International Standards Organization) clearly identifies a need for organizations to develop integrated management systems that address aspects such as product/service quality, employee safety, environmental performance and financial control. It defines a QMS as the organizational structure, accountabilities, corporate resources, processes and procedures necessary to establish and promote a system of continual improvement while delivering a product or service. The QMS is the organization, its people and all operational processes dedicated to meeting customer requirements. In a maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) operation, this means providing on-time turnaround and delivery of aircraft, 100 percent accuracy in the performance of work, courteous and helpful customer service while conducting operations in compliance with hundreds of regulatory and contractual requirements. Operators and their passengers who travel on these aircraft have several expectations — arriving alive (the most important criteria), arriving on time and arriving with a satisfactory travel experience. The QMS enables the organization to operate as an entity. ISO 9001:2008 highlights the importance of organizational leadership, a systems approach to management, people, process development, continual improvement, data analysis and supplier oversight. These eight fundamental quality principles form the foundation of an SMS.

Principle 1 – customer focus

Principle 2 – leadership

Principle 3 – involvement of people

Principle 4 – process approach

Principle 5 – systems approach to management

Principle 6 – continual improvement

Principle 7 – factual approach to decision making

Principle 8 – mutually-beneficial supplier relations

Safety Management – An Equal Partner with Quality

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) defines “safety” as a state in which the risk of harm to persons or property damage is reduced to, and maintained at or below, an acceptable level through a continuous process of hazard identification and risk management.1 The ICAO definition implies continuing measurement and evaluation of an organization’s safety performance and feedback into the management system. Measuring operational activity occurs both on the corporate level as safety and quality services departments analyze data received from multiple sources, but perhaps even more importantly, each functional area is assessing its operational activities to identify opportunities for improvement. This culture and passion for continual improvement is an essential change for safety practitioners in the way they approach safety management. In other words, a “well-managed operation is a safe operation.”

Many organizations have formally integrated the functions of safety and quality into a safety and quality management system (SQMS). Rather than operating in independent “silos,” these two organizations and respective functions may be merged into an intra-supportive group by integrating data collection, data analysis, risk management, corrective action, reporting and management review. This interim step to full integration may be challenging in that both organizations have uniquely different cultures that require a period of months or even years to achieve full harmonization. However, the effort will pay great dividends in that the different tool kits of the safety and quality disciplines may be integrated for the overall benefit of the organization. Although it may be a bit simplistic, the key to good safety performance is the application of quality principles through the organization. Stated differently, “quality” is the means to “safety.”

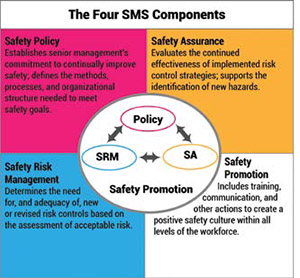

The concept of organizing an SMS into four components and 12 elements may be directly applied to quality. Each of these disciplines share common elements, but most importantly are the elements of change management and continual improvement. These two elements are essential and are now beginning to take on more importance throughout the aviation industry. Their unique applicability across all organizational disciplines validates their importance as a means for improving quality and safety, as well as other business processes. It should be noted that historically, the concepts of quality assurance and quality control in the aviation industry has proven helpful in identifying opportunities for improvement, system deficiencies, non-conformance to internal processes and procedures, and non-compliance with external regulatory requirements. However, by truly embracing change management and continual improvement, organizations will advance to the next level of success.

Change Management

Change management is an approach to transitioning individuals, teams and organizations to a desired future state3. The concept of change management is relatively new to the aviation industry. In fact, many organizations will rarely take the time to plan, organize and document change within the organization. These organizations will typically attempt to mirror an existing process at another location such as building a new maintenance base or expanding into a new region. A common philosophy is to rely on dedicated employees to spend the extra effort required to implement the change by “muscling” or “pushing” their way through the project to make up for the inadequate planning up front. ICAO states ,“A formal management of change process should identify changes within the organization which may affect established processes, procedures, products and services. Prior to implementing changes, a formal management of change process should describe the arrangement to ensure safety performance4.”

Although many aviation companies consider themselves agile and adaptable to economic or competitive changes, most of these change processes have not been formally documented throughout the organization. A company is either going one of two ways — getting better or getting worse, improving or deteriorating, staying ahead of competitors or slipping behind. Every company is changing. The crucial question is, “Is the leadership team guiding this change, encouraging improvement and investing in employee skills to accelerate change?”

There are two “speeds” at which change occurs. Most safety and quality practitioners deal with what may be called incremental change. This type of change is perhaps easier to control and relies on a culture of continual improvement with a passion for identifying soft spots or weaknesses in the operation and getting them fixed. In contrast, Robert Quinn describes transformational change in his book “Deep Change” as being essential to remaining competitive in rapidly changing environments.5 The aviation industry has evolved during the last 40 years through incremental change. Aircraft accidents have been reduced through incremental changes in cockpit automation and maintenance practices such as traffic collision avoidance systems (TCAS), weather radar, computerized tool control systems and the evolution of inspection checklists. Flight crew and maintenance technician training programs have also been improved through incremental change — through the development of full-motion simulators, maintenance resource management (MRM), electronic flight bag (EFB), OEM school houses, etc. Each of these innovations was triggered following recognition that a change to the way we do business was required to improve safety. Each of these industry initiatives began life as an option or a best industry practice and was ultimately embraced by regulatory agencies as an industry required standard.

At the other end of the spectrum, a transformational organization with an entrepreneurial culture will be eager and emotionally prepared to move to the next level. The deep change process requires that the team is ready and willing to take the risk of change — not knowing exactly what it will bring from them on a personal basis. There is a certain anxiety associated with the unknown, but the team has extraordinary confidence in their own skills to not only survive the deep change process, but to end up in a much better place at its conclusion. This group is willing to accept both corporate and personal risk (based on skilled analysis) to move the organization ahead of its competitors.

1 ICAO Safety Management Manual (SMM), Second Edition – 2009, paragraph 2.2.4

2 FAA: The Four SMS Functional Components - http://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/sms/explained/components/

3Kotter, J. (July 12, 2011). “Change Management vs. Change Leadership – What’s the Difference?” Forbes Online. Retrieved 12/11/11.

4ICAO Safety Management Manual (SMM), Second Edition – 2009, paragraph 6.6.4

Continual Improvement

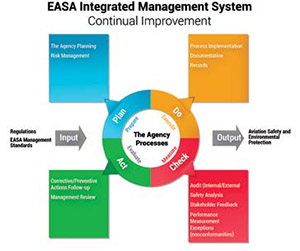

Every commercial enterprise must embrace the concept of continual improvement in order to survive, to effectively compete in the market place and to ensure survivability. Continual improvement is a characteristic of a learning culture that enables proactive risk management through process assessment and improvement. By definition, it is an ongoing effort to improve products, services or processes.6 The aviation community has begun to accept the Shewart cycle or plan-do-check-act cycle as an appropriate tool for continual improvement. Transport Canada, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and the FAA have embraced this tool for

application in a number of situations:

• As a model for continual improvement and change management

• When developing a new or improving the design of a process, product or service

• When defining a repetitive work process

• When planning data collection in order to verify and prioritize problems or root causes

• When implementing any change

• When starting a new improvement project

As an example of application, EASA has created an integrated management system based on the concept of the PDCA cycle. The PDCA descriptors may also be relabeled prepare, execute, measure and evaluate.

The Value of Alignment

ICAO describes safety as the result or consequence of the management of organizational processes. The first priority of any organization is to deliver products and services and to provide value to the customers. However, the regulatory community has little or no interest in whether the aviation service provider creates value for the investor or stakeholders. The primary focus of the FAA, for example, is that the organization delivers a safe service as measured by accident and fatality statistics.

Each organization must invest finite resources in efficient production to provide customer value and then balance this with an acceptable level of protection that preserves the equipment and people who deliver the product or service. The regulatory community is beginning to recognize that both production and protection must be balanced appropriately by airlines, maintenance repair organizations, airports, manufacturers and air traffic control organizations. Simply stated, if the organization elects to invest all of its resources and emphasis on production with little emphasis on safety and quality management, the organization will likely incur a significant number of incidents such as aircraft ground damage, employee injuries, regulatory violations and operational inefficiency.

5Deep Change by Robert E. Quinn, 1996 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 1

6ASQ: Learn About Quality — http://www.asq.org/learn-about-quality/continuous-improvement/overview/o...

It would appear apparent to a quality and safety professionals that there are obvious advantages of harmonizing the framework of QMS and SMS.

• A common design and strategy will make sense to the management team and individual employees. Insight into the function of a single system may be easily applied to the other three systems.

• A common template will remove many departmental barriers to standardized application of data collection and analysis tools to manage operational risks, to ensure regulatory compliance and to ensure adherence to operational procedures. The major difference between systems is that each group is focused on a different body of state law and responds to a different regulatory agency.

• A common risk management process will align the technical vocabulary throughout the organization.

• Integrating the four systems enables the organization to capture a holistic assessment of operational risks.

As international and/or state regulatory agencies formalize and advocate their new state safety programs (SSP) and service providers develop and implement complementary SMS/QMS, there will be a growing thirst for tools that enable the concepts of continual improvement and change management in the aviation industry. The aviation industry is on the cusp of recognizing the immense value of harmonizing QMS and SMS to both deliver high-quality products and services (production) while maintaining an ever-improving level of safety for the consumer (protection). Through this efficient integration of systems, aviation organizations will undoubtedly advance to the next level of success.

Christopher Young is vice president of helicopter aviation services at Professional Resources in System Management (PRISM). Young gained 21 years of aviation and leadership experience from the U.S. Navy, CJ Systems Aviation Group and Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation. He has more than 2,900 flight hours. As a SH-60B SEAHAWK instructor pilot for the U.S. Navy, Young acted as naval air training and operating procedures standardization (NATOPS) officer and SAR standardization evaluator. He also served as executive officer and commanding officer of several Navy Reserve units. Young is a commercial- and instrument- rated pilot in multi/single-engine helicopters and airplanes and has flown as a helicopter medical transport captain.

Christopher Young is vice president of helicopter aviation services at Professional Resources in System Management (PRISM). Young gained 21 years of aviation and leadership experience from the U.S. Navy, CJ Systems Aviation Group and Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation. He has more than 2,900 flight hours. As a SH-60B SEAHAWK instructor pilot for the U.S. Navy, Young acted as naval air training and operating procedures standardization (NATOPS) officer and SAR standardization evaluator. He also served as executive officer and commanding officer of several Navy Reserve units. Young is a commercial- and instrument- rated pilot in multi/single-engine helicopters and airplanes and has flown as a helicopter medical transport captain.

While at Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation, Young was a key manager in helping with the development of Sikorsky Aircraft’s SMS, performed compliance audits, developed a comprehensive human factors curriculum, and conducted aircraft incident investigations. He was also integral to achieving competitive excellence (ACE), the company’s continuous improvement process. Young was certified as an ACE associate and was the ACE coordinator for his department which repeatedly achieved the Gold Site level certification, United Technologies Corporation’s highest recognition level.

As vice president of helicopter aviation services at PRISM, Chris understands the unique complexities helicopter operators face when implementing an SMS. He offers practical guidance on conducting safety and quality analyses, hazard assessments, incident investigations, compliance evaluations and continuous improvement opportunities.

William “Bill” Yantiss is the executive vice president at PRISM. He began his aviation career as a U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot. During his 20-year military career, he had an opportunity to train pilots in the F-4D/E, F-5E, and F-15A/B. He has served in many leadership capacities that include check pilot, operational test and evaluation test pilot, F-15 program manager, academic/simulator training squadron commander and fighter squadron commander. Yantiss was a distinguished graduate from Air Force pilot training, earned “Instructor of the Year” and received an air training command “Well Done” safety award. He retired from the Air Force in 1989 as a lieutenant colonel. Yantiss was immediately offered an opportunity to experience and understand the unique Corporate Aviation industry while flying Beechcraft King Air and Lear 35 aircraft.

William “Bill” Yantiss is the executive vice president at PRISM. He began his aviation career as a U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot. During his 20-year military career, he had an opportunity to train pilots in the F-4D/E, F-5E, and F-15A/B. He has served in many leadership capacities that include check pilot, operational test and evaluation test pilot, F-15 program manager, academic/simulator training squadron commander and fighter squadron commander. Yantiss was a distinguished graduate from Air Force pilot training, earned “Instructor of the Year” and received an air training command “Well Done” safety award. He retired from the Air Force in 1989 as a lieutenant colonel. Yantiss was immediately offered an opportunity to experience and understand the unique Corporate Aviation industry while flying Beechcraft King Air and Lear 35 aircraft.

He joined United Airlines as a pilot instructor in 1989 and was quickly promoted to department manager. Shortly thereafter, he assumed staff responsibilities for both flight standards and flight safety. These short assignments have led to a 20-year career in developing safety, security, quality and environmental programs and management systems.

Yantiss was selected as vice president of corporate safety, security, quality and environment in December 2006. During two years in this position, he sponsored a number of initiatives that have significantly reduced operational risk by improving regulatory compliance, supplier oversight and safety management. He partnered with the FAA to publish the first SMS advisory circular, a guide to developing and implementing an SMS in any organization. He was also a key architect of the IATA operational safety audit (IOSA) program that is the “gold standard” for commercial airlines.