Risk Analysis for A&P Mechanics

Risk analysis for A&P mechanics? Really? What are we going to discuss now, 401k investments for the financially impaired? Not today, but we are on the right thought process. Risk analysis and risk management are terms more thought of in the same vein as mortgage brokers, investment bankers and financial advisors. If nothing else, the word management is there, so shouldn’t this be something for our boss to worry about and not us? Yes, the boss should worry about it and his or her boss and right on up the chain of command. But why shouldn’t we, the worker bees worry about risk also? After all, if something goes wrong, who has their name on the work that was done?

If we think about it, we are at risk every day in almost all that we do, from driving to and from work, to eating out. What are the chances of being involved in a fender bender? How about eating out and getting food poisoning? How about just being around other people and catching a cold or worse? We are so accustomed to certain risks that we put them out of our minds and don’t think of them as risks. They are just part of our lives.

As a member of HAI’s Technical Committee, I have the privilege of attending meetings with a terrific group of helicopter maintenance professionals who bring a tremendous amount of expertise and experience to the table. One of these individuals is Don Lambert, senior director of technical integrity with Air Methods Corp. At our October 2012 meeting hosted by Bristow Academy in Titusville, FL, Lambert brought in a worksheet on risk assessment for technicians that got me thinking. (Yes, I know that can be dangerous.) If we could apply a certain level of risk analysis to the work we do every day on the helicopters/components entrusted to our care, how much better and safer could we do our jobs, and in turn, improve the helicopters safety in flight?

To begin, we need to define just what risk analysis is. According to ISO 31000, risk analysis is the identification, assessment and prioritization of risks (defined as the effect of uncertainty on objectives, whether positive or negative), followed by coordinated and economical application of resources to minimize, monitor and control the probability and/or impact of unfortunate events or to maximize the realization of opportunities. Wow! That’s a mouthful. In simple terms, we could say that in our profession there are risks that we encounter all the time, but we are so used to them that we do not think of them in terms of risk. The key words above are to minimize, monitor and control the probability and/or impact of unfortunate events. In our line of work, unfortunate events tend to lead to time, cost and safety issues, and those are events that we definitely want to minimize and/or avoid.

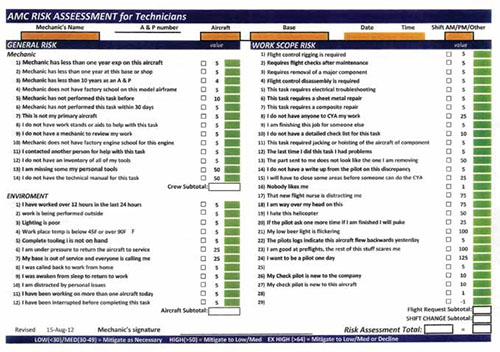

When performing risk analysis with respect to performing maintenance on an aircraft, engine, gearbox, etc., the risk involved could be so minor as to be transparent or seen as no risk at all. The risk could also be seen as being so major that the work should be declined. How do we know what level of risk we could encounter before it happens? The chart that Lambert showed me helps us to do just that — evaluate the risk for the job to be done before the job starts or is even accepted. The chart breaks down the risk analysis into two parts. Part one is a “general risk” section and part two is a “work scope risk” section. The form’s header has space for the mechanic’s name, A&P number, aircraft, base location, date, time and shift.

The general risk section involves questions that are applicable to the mechanic and the work environment. The work scope section involves questions that are applicable to safety of flight and the shift involved. Now, in all fairness, some of the questions shown on the form are ridiculous, but the form at this time is not finished and some questions are there just as fillers. They should not in any way be thought of as legitimate questions or feel that any operator would actually think in these terms.

A series of questions is asked in each part and assigned a numerical value. After filling out both sections of the form, the point values assigned are totaled. There is a space to fill in a number for that question, so in fact, what the mechanic filling out the form would be doing is assigning a “risk” value to the question being asked. The lower the number filled in, the lower the risk on that question. There are four subtotals that are added together that give the risk assessment for that particular task. The subtotals are categorized as crew subtotal, aircraft subtotal, flight request subtotal and shift change subtotal. The overall risk is categorized as:

Low risk is a point value less than 30

Medium risk is a point value between 30 and 49

High risk is a point value between 50 and 64

Extremely-high risk is a point value greater than 64

The point values totaled for a given task indicate that there is low risk and that indicates you do the task. Medium risk tells the mechanic he or she needs to take appropriate action to reduce the risk to low risk before continuing. High and extremely-high risk indicates that action needs to be taken to reduce the risk to low/medium levels. That may also indicate that a different mechanic with a different set of skills performs the task or that the task is not done at that facility at all.

The beauty of the form is that it can be customized for any type of operation. There are some tasks that are the same, regardless of location, who operates the aircraft or what its mission is. There are other tasks that might be mission important for an EMS operator and others that are applicable to an MRO performing an engine overhaul. In either case, risk is always a factor and this is another tool that can be utilized to lower risk on the job.

Tell us what is done at your facility to lower risks. What do you think of the form? Please share your thoughts with Lambert and me. As members of HAI’s Technical Committee, we value your input and are there to represent you.