The Impossible Helicopter of 1909 - Emile Berliner [1851-1929] & Igor Sikorsky [1889-1972]

“The helicopter is much easier to design then the aeroplane but it is worthless when done.”

Attributed to Wilbur Wright, 1909

Witnesses and photographs recorded the Wright brothers’ first flights at Kitty Hawk in 1903, establishing a historic moment in time. Each aviation technological advancement traces its origin to 1903, specifically the progression of fixed-winged aircraft. No such “moment in time” for first flights is as famous nor as universally accepted for rotorcraft. Described by aviation author, James Chiles, monetary prizes, science awards and historic recognition could be rightfully claimed only when a machine,

a) Could lift its own weight plus payload

b) Hover with (good) control

c) Move through the air fast enough for travel

d) Land safely with a dead engine (autorotation)

Historians agree that these criteria were finally met during the 1920s although prior attempts were nothing short of valiant.

“The way to fly is straight up.” Emile Berliner

Emile Berliner [1851-1929) & J. Newton Williams [1840-1928]

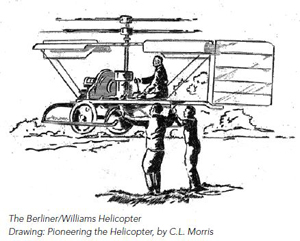

In Maryland in June 1909, Emile Berliner, 59, and J. Newton Williams, 69, tested a full-scale helicopter which reportedly rose a few feet and hovered, carrying Williams as pilot. No photographs of the lift-off exist but experts agree that it was possible with the stabilizing hands of assistants.

Independent of each other, Berliner and Williams each made successful small vertical flight models but their real challenge was power for a full-scale machine. Williams founded a factory in Connecticut in 1892 which produced typewriters of his own invention. Having an adventurous background fighting in the “Indian Wars” for the Union Army, Williams, a talented mechanic, was fascinated with manned flight, and left his business to a partner in 1905, to build a helicopter.

Unsuccessfully using his own power plants between 1905 and 1908, the white-haired Williams borrowed a V-8, 40hp engine from its creator, Glenn Curtiss of Hammondsport, NY. When this failed to improve Williams’ invention, he moved to Washington, D.C., and soon met Berliner who welcomed another mechanical mind, not to mention a man brave enough to be a test pilot.

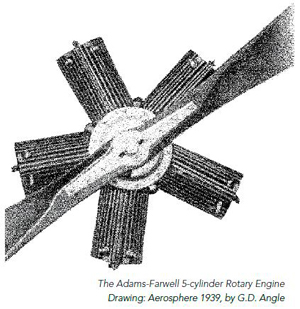

Between 1907 and 1908, Berliner experimented with helicopter models in Maryland. A German immigrant, Berliner had already patented his Gramophone and other inventions with financial success. In 1907, he commissioned the Adams Company of Dubuque, Iowa, to build a five-cylinder, 36hp rotary air-cooled engine known as the Adams-Farwell to power his full-scale helicopter.

Founded in the late 1880s, the Adams Company’s general superintendent was F. Oliver Farwell. Farwell is attributed with the 1896 design of their first three-cylinder rotary engine that was used initially on wagons and eventually powered the Adams Motor Cars of 1903 to 1905. Berliner may have foreseen the potential use for a helicopter based on advertisements which claimed that the Adams-Farwell engine “operated with very little vibration.” He bought two modified Adams-Farwell five-cylinder engines for tests he intended to conduct on the Aeromobile, a wheeled frame with propellers. By 1909, he and Williams were ready to take to the air, leading to one of the first uses of the rotary air-cooled engine on a flying machine.

The Berliner/Williams Helicopter

According to helicopter historian Frank Ross, the Berliner/Williams machine of 1909-1910, “was simple in construction.”

“It had a small rectangular frame in the center of which the engine was fastened. Directly to the rear was a seat for the pilot. Rising straight up from the engine was a shaft on which two rotors were fastened, one above the other, rotating in opposite directions. For landing purposes, the helicopter had two large wheels at the front end of the frame and a sort of tail skid beneath the pilot’s seat.”

The machine, weighing more than 600 pounds, survived several tests, but after injuries to his helpers Berliner lost enthusiasm and halted the project. Williams continued alone for several years but made no further advancements. Berliner and his son Henry returned to helicopter designs with greater success in 1919.

Meanwhile, a Russian young enough to be a grandson to Berliner or Williams was contemplating his own helicopter design.

The Impossible Helicopter!

“To invent a flying machine is nothing; to build it is little; to make it fly is everything. You will waste your time on a helicopter. My advice is to work on an airplane. That is much more promising.”

Captain Ferdinand Ferber

French Army, To Igor Sikorsky ~1909

Igor Sikorsky, born in Kiev, Russia, in 1889, was just a teenager when he decided to devote his life to the science of aviation. Sikorsky’s father and mother, who both held degrees in medicine, encouraged him to continue studying a wide range of subjects from music to chemistry. But young Sikorsky’s heart was captured by the successes of the Wright brothers and by Louis Bleriot’s crossing of the English Channel in a monoplane in July 1909. With both a solid education and a brief career in the Russian Navy, Sikorsky announced to his family that he was going to invent a helicopter.

Sikorsky converted a garden house into his “shop” on the grounds of his family home in Kiev, and built his first helicopter, the “H-1.” Apparently unimpressed with the new French air-cooled engines, he reasoned that his biggest challenge was to find a lightweight, reliable power plant, concluding, “Helicopters are impossible; all engines are bad.” Nevertheless, Sikorsky chose a radial water-cooled power plant and put hammer and wrench to work. “The body of the machine was a square wooden frame,” writes Sikorsky’s biographer, Frank DeLear. “Attached to one side was the [25hp] Anzani engine” which he had purchased in France, as the least “bad” of all engines then made. The pilot would sit opposite the engine, and,

“In the center was a transmission box, which would deliver the engine’s power to the rotor blades overhead. Two hollow metal shafts, one inside the other, ran vertically up from the transmission. Each shaft was attached to a two-bladed lifting propeller or rotor. A pulley and belt system drove the rotors, which turned in opposite directions. The blades were held firm by piano wires above and below. The wires could be shortened or lengthened to change the pitch, or lift, of the blades. Control was to be provided by small wing surfaces placed in the downwash of air from the rotors.”

Standing near his machine, Sikorsky turned on the engine and made many adjustments that kept it from shaking apart or tipping over. “Igor continued to test his helicopter for over two months,” wrote DeLear. “The machine danced and slid along the ground, kicking up clouds of dust and leaves, and obviously supporting much of its own weight.”

Although Sikorsky knew the “H-1” would never get off the ground with a pilot, he was fueled with renewed confidence that his next design would be successful. He returned to Paris, and brought back another 25hp Anzani engine. That winter, he attached propellers and an engine to a sled and swooshed through Kiev’s snowy streets for the purpose of acquiring a sense of flying. He designed a second helicopter, “H-2” and an aeroplane, “S-1,” during 1910. Still unable to lift its weight plus a pilot, Sikorsky’s “H-2” also failed. At age 21, Sikorsky decided to abandon helicopter design temporarily and concentrate on fixed-wing aircraft. Following great success with his aeroplanes, Sikorsky did not return to designing another helicopter until 1939.

Correcting Aviation History

Although Emile Berliner was a brilliant inventor, several published references incorrectly identify him as the designer of the Adams-Farwell engine. It has been speculated that the 1904 Farwell engine influenced the successful Gnome rotary aircraft engine developed in 1906 by the Seguin brothers of France.

Many technical histories of engines also incorrectly identify the Adams-Farwell as the first rotary engine used in an aeroplane piloted by Charles K. Hamilton at Seattle in 1909. “Not so!,” according to Hamilton’s biographer, John Sipple, who documents Hamilton’s first flights at Seattle in March 1910 while employed for Glenn Curtiss’ exhibition team. Neither Curtiss nor Hamilton is known to have used an Adams-Farwell engine.

Next: “Untethered Success! Lift-off During the 1920s”

Giacinta Bradley Koontz (“Gia”) is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and the History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.