Untethered Success – Lift-Off During the 1920s

At Last – A Real Helicopter!

Although they had advanced the theory of vertical flight, early inventors like Igor Sikorsky failed to create an aircraft that satisfied the requirements of the Federation Aeronatique Internationale (FAI), the aviation world’s official bookkeeper. Nevertheless, there were plenty of odd birds among aviation enthusiasts determined to defeat gravity and fly straight up — and return down safely. Contributing inventors had emerged from several nations by the 1920s. Of these, Jacob C. Ellehammer was a stand-out among his less successful contemporaries.

Jacob C. Ellehammer (1871-1946)

Curious and experimental as a youth, Ellehammer began working as an electrical engineer directly after his formal education in his native Denmark. His talents for all things mechanical were applied to the tiny precision mechanisms of watch making and the new science of X-ray equipment. Far from watches and a medical lab, Ellehamer also designed and built a motorcycle and the engine to run it. Seemingly independent of aeroplane development by the Wright brothers, Alberto Santos DuMont of France and others, Ellehammer designed and flew short hops in his “semi biplane” and “bi-plane” in 1905, becoming the first to fly in Scandinavia.

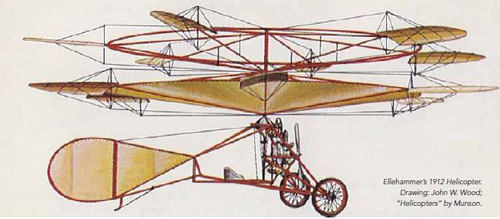

By 1910 the world had become air-minded. Like American Glenn Curtiss and many other men and women who designed and/or raced motorcycles, Ellehammer soon applied his engineering talent to aircraft development. Unlike most of his contemporaries consumed with building monoplanes and biplanes, Ellehammer was intrigued by the potential for vertical flight. By 1911, he had created a scale model of a rotary-winged aircraft and in 1912 built a full-scale machine. For safety, privacy and control, he tested his unmanned aircraft inside a building where wind gusts would not be a factor. From several feet away, Ellehammer used hand-held controls connected to his machine which was powered by a 6 hp engine of his own design. His first successful flights of vertical hovering with more or less controlled landings were witnessed by many, including Denmark’s Prince Axel (1888-1964). Perhaps due to Ellehammer’s influence, the young royal’s early interest in aviation continued for decades — he became the Director of the Scandinavian Airlines System.

Odd But Graceful

Between 1912 and 1916, Ellehammer’s invention progressed from unmanned hops to a helicopter with him on board at the controls during several test flights. The significance of his invention was in the eye of the beholder. It was briefly described by one historian merely as “an odd but graceful little helicopter with stubby rotor blades.” Historian Kenneth Munson was obviously more impressed:

“The 6 hp engine drove both the rotor system and a conventional propeller. The lifting rotors were of an ingenious pattern, consisting of two contra-rotating rings, each of more than 19 feet in diameter, the lower one being covered with fabric to increase the lift. At regular intervals round the perimeter of the wings were six vanes, each about four feet long and two feet wide and pivoting about its horizontal axis. The rotor system was driven via a hydraulic clutch and gearbox, all designed by Ellehammer, and the rotor vanes’ angle could be altered in flight by the pilot –— an early example of cyclic pitch control.”

“The 6 hp engine drove both the rotor system and a conventional propeller. The lifting rotors were of an ingenious pattern, consisting of two contra-rotating rings, each of more than 19 feet in diameter, the lower one being covered with fabric to increase the lift. At regular intervals round the perimeter of the wings were six vanes, each about four feet long and two feet wide and pivoting about its horizontal axis. The rotor system was driven via a hydraulic clutch and gearbox, all designed by Ellehammer, and the rotor vanes’ angle could be altered in flight by the pilot –— an early example of cyclic pitch control.”

After this helicopter was destroyed during a test accident in 1916, Ellehammer abandoned vertical flight inventions. His imagination soared again in 1930 with novel designs for a parasol monoplane with contra-rotating rotors within its wings, and a helicopter powered by an air compressor and a radial engine. Neither of these designs went beyond scale models, but this remarkable inventor had already contributed novel and practical technology for use in vertical flight aircraft.

Up in a Crow’s Nest

During 1915 and 1916, Lt. Stefan von Petroczy of the Austrian Army, in association with Theodore von Karman and Wilhelm Zurovec, set out to design a replacement for the military’s existing tethered observation balloons. What was needed was an engine-powered vertical lift machine that could fly from one location to another. Before advancing to “flight,” Petroczy, Karman and Zurovec tackled “lift.”

Using their initials, the machine became known as the “PKZ.” It was designed to carry an observer standing inside a barrel-shaped crow’s nest (or “tub”) above the rotors and engines. The observer was equipped with spy glasses, a gun and a parachute on the optimistic chance that he became detached from his aircraft at high altitude before becoming a target for enemy gunfire. The frame weighed more than 3,000 pounds, and on each of three “arms” were engines to drive two contra-rotating rotors that were 19 feet in diameter. Secured to the earth by steel cables, Petroczy was more certain he could go up than safely down and therefore, according to one source, his machine was brought to a soft landing on inflated pontoons.

Many witnesses watched successful, tethered, unmanned “flights” of which the highest was 150 feet above ground and hovering for one hour. When the machine was wrecked during further tests, the project was abandoned and historians have largely overlooked the entire invention.

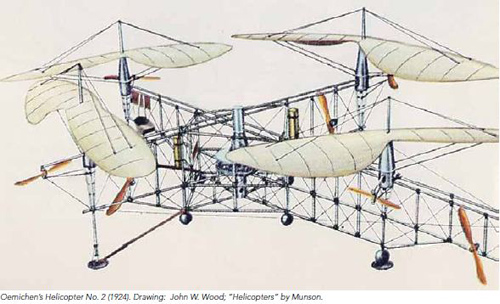

The basic elements of lift and control were ultimately achieved during the early 1920s by two émigrés to the U.S., inventors Emile Berliner (1920) and George de Bothezat (1922), and by Etienne Oehmichen of France. Oehmichen initially suspended his rotorcraft from a gas-filled balloon. Impractical, clumsy and even dangerous, he soon abandoned the design but not his passion for vertical flight. Following further development and testing between 1922 and 1924, Oehmichen’s machine established the first helicopter distance record officially recognized by the FAI. With four lifting airscrews and five propellers, it rose off the ground and flew more than 1,000 feet on April 17, 1924, using a Le Rhone, 180 hp engine. His record was short lived — the next day it was broken by none other than royalty from Spain.

Worth Mentioning

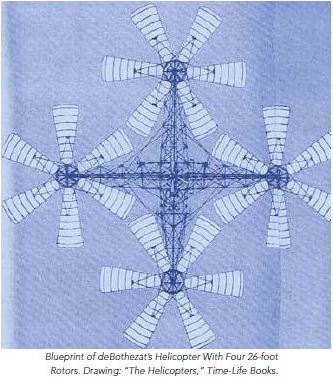

During 1924, Berliner affixed two coaxial counter-rotating rotors on the wings of a Nieuport biplane with “moveable vanes” and piloted his hovering and un-tethered aircraft in a demonstration for the U.S. Army. The Army also considered a helicopter designed by de Bothezat, whose invention has been described as an “X-shaped structure, more than 60 feet wide with four huge fan-shaped rotors mounted at each corner.” With de Bothezat at the controls, officers at McCook Field in Ohio observed dozens of demonstrations as he managed to get 15 feet off the ground, albeit uncontrolled. According to some historians, de Bothezat was brilliant, but temperamental and “difficult to work with.” Like Bothezat, his helicopter was also complicated and unreliable and the military lost interest.

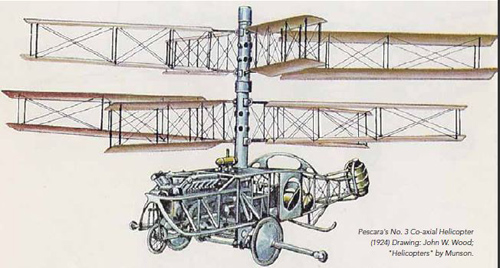

Unfettered by politics, personalities and financial difficulties was the Marquis Raul Pateras Pescara of Spain who began experimenting with helicopter-type machines between 1919 and 1920. His unmanned, tethered aircraft, “No. 1,” was considered unstable and clumsy, weighing more than 1,000 pounds. It had a combination of 24 rotors and blades and used an under-powered engine. Pescara moved to France in 1922; there, over the next two years, he modified his design twice, naming them “No. 2” and “No. 3.” These helicopters used larger rotors and a 180hp Hispano-Suiza engine and were capable of controlled flights of more than 10 minutes. On April 18, 1924, flying “No. 3,” Pescara bested Oehmichen’s FAI record by flying 2,000 feet. “The significance of this achievement,” wrote Munson, “lay in the fact that Pescara’s machine did not rely on conventional propellers rotating in the vertical plane to give the aircraft forward motion. Instead, the pitch of the 16 lifting surfaces could be altered in flight by warping them, and the rotor head could be tilted to give the blades a degree of forward thrust. The Pescara No. 3 exhibited the first convincing demonstration of the principles of cyclic and collective pitch control. Autorotation of the rotors was also provided for in the event of engine failure.”

Pescara was soon overshadowed by another Spaniard, Juan de la Cierva, already developing the most significant advancement in vertical flight to date.

Next: The Auto-Gyro and Beechnut Gum